September 28, 2017

"Shogun" revisited (3/4)

Shogun provided plenty of material for the easily outraged.

The propensity to treat a foreign culture as an extended episode of Ripley's Believe It or Not! is known as "Orientalism." It's a valid criticism, though keeping in mind that that the biggest Orientalists in the world are Orientals. Ditto "Occidentalism."

The more blatant Orientalist sins are found in the middle arc of Shogun, which, frankly, slows to a drag. The political scheming and deal-making that would soon shatter the fragile regency and lead to the Battle of Sekigahara was going on elsewhere. So Blackthorne hasn't much to do.

Instead we get a tedious soap opera, poor language acquisition skills, and a crash coarse in Nihonjinron, a nativist philosophy that was all the rage in the 1970s and 1980s. Nihonjinron argues that everything about Japan is unique, special, and unlike anything else in the world.

And every Japanese, by dint of being Japanese, is born a zen master.

Not only James Clavell, but pretty much the entire media establishment bought into it hook, line, and sinker. As a result, any silly assertion could be justified on the grounds that it was "Japanese," including all that pop-psychology blather about "living in the moment" and whatnot.

In part, I believe that writers of Clavell's generation were trying to comprehend Japan's role in WWII. Thus the huge influence of Ruth Benedict's The Chrysanthemum and the Sword. Written during the war, it helped spawn the modern Nihonjinron movement after the war.

I remember my Japanese professors of Japanese being the most annoyed about the absurd business with the pheasant and the depiction of seppuku (harakiri) and kiri-sute gomen (切捨御免) as being well-nigh ubiquitous.

Meaning "to cut down without regard," the latter refers to the "right" of the samurai "to strike with sword at anyone of a lower class who compromised their honor." As portrayed, it's about as historically accurate as gunfights at high noon were in the 19th century western United States.

Meaning, it happened. Now and then. Certainly not as often nor as casually as suggested in Shogun (and countless home-grown samurai actioners). Killing commoners was a bad idea in an agrarian society with limited arable land and a staple crop that requires a lot of care and nurturing.

Actual armed conflicts were more likely to erupt between high and low-ranked samurai, hence the term gekokujou (下剋上), meaning "juniors dominating seniors." The legendary "revenge of the 47 ronin" began with two high-ranked provincial lords getting into a tussle in Edo Castle.

The Meiji Restoration was in large part driven by lower-ranked samurai revolting against their masters, up to and including the Tokugawa shogunate.

But let's make love, not war. Orientalism doesn't get any sillier than the scene in which Blackthorne is offered a foursome. The only difference with practically the same material in You Only Live Twice is that James Bond is randier than Blackthorne. And takes himself less seriously.

Of course, the message of this Oriental "exoticism" is that everybody is having better sex than stuffy old us. Though given the current birth rate in Japan, that particular message seems to have gotten lost somewhere along the line.

We also get a de rigueur mixed-bathing scene. As far as that goes, you'll have to look long and hard to find a mixed public bath in Japan these days, though it was once commonplace.

U.S. Consul Townsend Harris was shocked by the practice back in the 1850s. He was reassured by one of his more anthropologically-minded friends that "the chastity of Japanese women" was due to "this very exposure that lessens the desire that owes much of its power to mystery and difficulty."

Which brings us to a running joke in the Shogun miniseries that happens to be pretty spot on. Again, it was Townsend Harris who observed that the Japanese "are a clean people. Everyone bathes every day."

Back in the 16th century, Europeans didn't. So the first time he's told to wash his smelly self off, Blackthorne reacts as if he's been told to jump into a volcano. Though it doesn't take him long to think better of the practice (especially when he gets to share the tub with Yoko Shimada).

Blackthorne never quite conquers the conjugation of "to be," but the o-furo is one cultural practice he has no problem accommodating himself to.

Related posts

Shogun revisited (4)

Techno-orientalism

Dances with Samurai

Japan made in Hollywood

Labels: history, japanese culture, shogun, social studies, television reviews

September 24, 2017

Blue Orchid (4)

Labels: 12 kingdoms, hisho, translations

September 21, 2017

"Shogun" revisited (2/4)

Gessel discusses the experience in the lecture featured below (the audio quality is unfortunately poor).

Shogun is also based on a novel. James Clavell did his homework too. But nobody sells 15 million copies of anything conducting a graduate course on medieval Japanese history and anthropology. So Clavell methodically runs through a checklist of every "educated" stereotype on the subject.

And probably promulgated a few new ones. This isn't necessarily a bad thing. Stereotypes persist because of their utility. If 15 million people can be persuaded to read a 1152 page melodrama about Japan's Warring States period at the end of the 16th century, maybe they'll be game for more substantive fare.

But how does the miniseries otherwise hold up as a cinematic experience? Sure, it clunks rather loudly at times. But all things considered, better than I expected it would.

Shogun looks like a NHK historical drama from the early 1980s. That's a criticism and a compliment. It was shot at Hikone castle, Himeji castle, and at the legendary Toho, Shochiku, and Daiei-Kyoto Studios. It's nice to see real Japan in a movie about Japan.

The Last Samurai was shot in New Zealand, 47 Ronin was shot in Scotland and Hungary, and Silence was shot in Taiwan. This isn't all the fault of Hollywood. Japanese politicians haven't quite grasped the idea of local film commissions that recruit big budget film productions and cuts through the red tape on their behalf.

One advantage of building sets and shooting in places like New Zealand is not having to matte out the backgrounds. As Akira Kurosawa once noted, "Japan's penchant for power lines and retaining walls has left little unspoiled scenery for movie makers."

Shogun director Jerry London employed the same cheats as Masato Harada did shooting his 2017 historial epic, Sekigahara: high and low angles with tight fields-of-view (which is less annoying when the castle in the background is a real Japanese castle).

Shogun co-star Yoko Shimada wears too much makeup and the wigs aren't terribly convincing. Again, what you'd expect in a NHK drama from forty years ago. They've greatly improved in both departments since, though the chonmage (丁髷) is still a challenge.

The chonmage hairstyle lasted well into the 19th century. It's essentially a reverse Mohawk, hard to pull off without leaving a bump across the forehead. Issei Takahashi in Naotora wears one about as good as I've seen—except when viewed from the back.

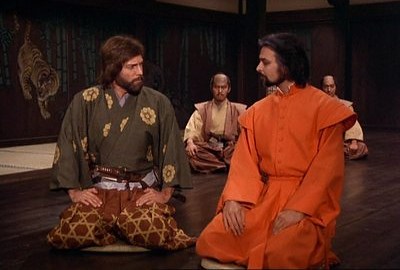

But it's a costume drama, so—costumes. Richard Chamberlain wears a hakama quite nicely. But knowing a little more history (and being exposed to a lot more Japanese television) than I did back then, what first upset my suspension of disbelief was the casting of Ishido.

There's no arguing with Toshiro Mifune as Toranaga, nee Tokugawa Ieyasu, though sans the chonmage that in contemporaneous portraits Ieyasu is always depicted sporting. I suspect that Mifune, as well as Kaneko, simply didn't want to go through all the bother, the kind of thing an actor can get away with if he's a big enough star.

But casting Nobuo Kaneko as Ishido only made me grin. The problem is that Nobuo Kaneko resembles a Japanese Edward G. Robinson. Maybe they wanted to be obvious and have a heavy play the heavy.

Ishido's historical equivalent is Ishida Mitsunari, who led the Western armies against Ieyasu's Eastern forces.

Mitsunari was only forty-one at the Battle of Sekigahara. He was a capable administrator who single-highhandedly kept the regime viable as Hideyoshi turned into a paranoid Shakespearean villain, executing anybody who challenged his legitimacy or threatened the succession of his son and only heir.

Mitsunari made a lot of enemies as Hideyoshi's enforcer. He also lacked battlefield experience, not having fought in Hideyoshi's two pointless Korean campaigns. As a result, keeping his allies on the same page was like herding cats. Many simply disliked Ieyasu more than they disliked Mitsunari.

Ieyasu as well usually left the fighting to others. A wily politician and negotiator, he convinced (bribed and coerced) several of Mitsunari's generals to either sit out the fight or defect to his side. The cataclysmic battle was over in a single day, despite half of Ieyasu's army arriving a day late.

As one of history's great might-have-beens, Mitsunari has long been ensconced in the pantheon of Japan's heroic losers. As such, he is invariably played by a dashing young actor, like Shun Oguri's portrayal of Mitsunari in Tenchijin (also sporting a great chonmage).

In the run-up to the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Mitsunari and Ieyasu jostled for political control of the regency created by Hideyoshi before his death. Sort of a Japanese version of The West Wing circa 1599. Alas, that's not the kind of material to make an American miniseries about.

There not being enough time or budget to show the battle itself, we're simply told about the subsequent events. This is unfortunate, considering that Adams himself removed the cannon from his ship, accompanied them to Sekigahara, and commanded the battery. Ieyasu had many reasons to prize the man's company.

So in order to place our protagonist in constant peril, Shogun exaggerates the importance of the Jesuits and the Portuguese in the months before Sekigahara. They mostly operated in and around Nagasaki. These confrontations foreshadow the fate of Japan's Christian community and the disastrous war soon to engulf Europe.

And Blackthorne's verbal spats with Father Alvito (Damien Thomas, whose Japanese isn't as "native" as his backstory suggests but is nevertheless quite good) make for better drama than the melodramatically overwrought romantic interludes with Mariko (Yoko Shimada).

Mariko is far more interesting as a spot-on illustration of the highly syncretic nature of religion in Japan, which can seamlessly blend Buddhist practice and Christian belief without a second thought. In fact, this may be the most accurate reading of Japan's contemporary culture in the miniseries.

But speaking of melodramatic excesses, rumors of conspiracies to assassinate Ieyasu really were rife. Though they never materialized, the Machiavellian Ieyasu leveraged them to his own advantage. And so do writers of historical fiction, such as Keiichiro Ryu's Kagemusha Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Related posts

Shogun revisited (3)

Techno-orientalism

Dances with Samurai

Japan made in Hollywood

Labels: history, japanese culture, japanese tv, language, nhk, shogun, television reviews, translations

September 17, 2017

Blue Orchid (3)

The water-channeling properties of the beech tree is called "stemflow."

Stemflow is the flow of intercepted water down the trunk or stem of a plant. Stemflow, along with throughfall, is responsible for the transferal of precipitation and nutrients from the canopy to the soil. In tropical rain forests, where this kind of flow can be substantial, erosion gullies can form at the base of the trunk. However, in more temperate climates stemflow levels are low and have little erosional power.

The Japanese chinquapin is Castanopsis cuspidata. The camphor tree is Cinnamomum camphora, "a large evergreen tree that grows 60 to 100 feet tall. The leaves have a glossy, waxy appearance and smell of camphor when crushed." The Chinese hackberry is Celtis sinensis.

The ranka is a made-up word, created from the kanji for egg/ovum (卵) and fruit (果).

Labels: 12 kingdoms, hisho, language, science, translations

September 10, 2017

Blue Orchid (2)

Like me, you're probably going to learn more about the beech tree from this story than you ever expected. My own research aligns well with the author's descriptions. For example:

When milled into larger boards, beech tends to have more knots and defects than birch. Beech is more likely to suffer from decay than birch; it also may show mineral discoloration or "spalding," which is a type of decay or fungus.

Labels: 12 kingdoms, hisho, science, translations

September 07, 2017

Trust but financially verify

In 2015, there were 58 total organ transplants in Japan, versus over 30,000 in the U.S. Though Japan is a great place to get an inexpensive MRI or CT scan (technology, natch).

No, I'm talking about mooching off one's friends and relatives. The term du jour is "parasite single." Though it is constrained by certain cultural boundaries. The most common (dramatically speaking) is clearing debts and securing loans. The latter is a recurring dramatic trope: person X cosigns for person Y, who then defaults putting X in a tight spot.

Thereupon follows the trope of running out on one's debts, something that is more plausible in a country where so much of the financial system remains cash-based and bankruptcy is seen as the worse of the two alternatives. A national ID number system was only recently introduced.

A recent NHK morning melodrama began with the family decamping to the Noto Peninsula (the far side of the Moon) after the father defaults on a loan. It ends with him defaulting again (because his guarantor turned out to be crook), except this time he goes through a formal bankruptcy. This is depicted as the higher road but a tougher choice than in the United States.

In any case, considering the kind of high-tech business he was in, in Silicon Valley, he would have secured venture capital to start with, and at worse would have had to give up a controlling interest in the company. But the whole venture capital concept—giving money to strangers based on the strength of their ideas—hasn't really caught on in Japan.

Only recently has become possible to rent an apartment in Japan without a co-signer and the equivalent of a year's rent in advance. In the current NHK morning melodrama (which takes place during the 1960s), a girl renting a room in a boarding house (not an apartment) has her previous and future employer co-sign the lease.

The United States, by contrast, because of its heterogeneous nature, evolved a "trust but verify" financial culture that makes it possible to invest in a person's resume rather that in who he's related to, and doesn't stigmatize risk-taking as long as the risk is understood. The venture capitalist accepts from the start that nine out of ten investments will fail.

The United States, by contrast, because of its heterogeneous nature, evolved a "trust but verify" financial culture that makes it possible to invest in a person's resume rather that in who he's related to, and doesn't stigmatize risk-taking as long as the risk is understood. The venture capitalist accepts from the start that nine out of ten investments will fail.This gets back to the intricacies of the mooching culture, which leads people to blindly trust "relations" even when the relations may turn out to be strangers. The result is an epidemic of what's called "Ore, ore" ("It's me") fraud. It's gotten so bad at times that police have been stationed at ATMs to ask the elderly why they are withdrawing money.

And yet, the deeply-seated cultural inclination, especially among the older generation, to trust "family" and to avoid public scandal, has made these crimes surprisingly difficult to curtail in a country that can rightfully boast of having one of the lowest crime rates in the world.

Labels: economics, japanese culture, law, nhk, politics, social studies

September 03, 2017

Blue Orchid (1)

In northern India, a particular species of bamboo flowers all at once every 48 years. The sudden abundance of bamboo seeds causes the rat population to explode. Once the rats have eaten their way through the bamboo, they turn on the granaries and paddy fields.

In the past, this phenomenon triggered famines. Now the cycles can be calculated and anticipated, but it's still a big problem every half-century.

Under the feudal system, a fief was "granted by an overlord to a vassal who held it in return for a form of feudal allegiance and service." In the Twelve Kingdoms, income from the fief pays a civil servant's salary. Apparently, he is also responsible for the wages of his subordinates.

A yaboku tree (野木) is the wild version of a riboku tree (里木). There are two types of yaboku: yaboku from which plants and trees are born, and yaboku from which animals are born. See chapter 53 of Shadow of the Moon.

Labels: 12 kingdoms, hisho, science, translations